Also I would like to pay special tribute to Shaikh Mustafa Ismael, a reciter who I feel has had the most impact in the field of Quranic recitation during the last 50-100 years. He has left behind many fans, enthusiasts, and imitators in all parts of the world such that his legacy still thrives today.

On this note I plan to also post many videos and pictures of the 'Saloon Ahmad Mustafa'. A place that has become the 'musical' school of Mustafa Ismael in Masr Gadeed/Cairo. It is a place where many great reciters and enthusiasts come to discuss, listen, and learn about Sh. Mustafa Ismael.

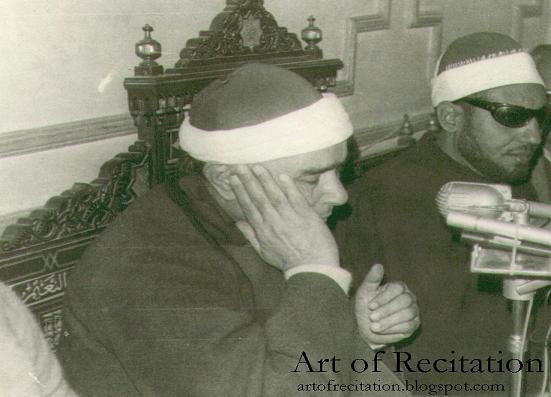

A rare picture of Sh. Mustafa Ismael.

Here is good article that talks about people I will profile in future posts:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Once, Sheikh Mostafa Ismail’s recitation of the Qur’an was enough to stop anyone in their tracks. Today, on the centenary of his birth, his followers are struggling to keep alive his tradition of melodic recitation. Will religious conservatives relegate an Egyptian tradition to the dustbin of history

One day, a stranger happened to be passing through the village of Mit Ghazal in Gharbeya governorate when he heard the voice of a little boy reciting Qur’an at a kuttab. The man stopped, then took the boy home, along with his tutor, to speak with his father, where he advised the father to keep teaching the child the Qur’an because he was going to become one of the best reciters in recent history.

That was in 1911 by 1920, the little boy named Mostafa Ismail was well on his way toward becoming one of the most celebrated Qur’an reciters Egypt has ever known.

“You have to know that his voice at the very beginning was very different from what you hear in available recordings,” says Sheikh Mostafa Ismail’s son, Wahid. “The earliest recitations available are from the 1940s but he became a professional in 1920, at the age of 15.

“Twenty years ago, I met a man who had known him at the time. He told me, ‘I swear to God your father’s voice when he was 18 was the most beautiful voice anyone had ever heard. If a bird was flying over the sowan [tent set up for bereaved to receive condolences], it would have stopped in mid-air to listen,’” he says.

This year marks the centenary of the Sheikh’s birth (he came into the world on June 17, 1905), and while the anniversary has not been celebrated by the official media — except in a short segment on the daily talk show El-Beit Beitak — Sheikh Ismail’s fans and family are certain that the future will only bring more appreciation of his musical genius.

The unofficial celebration in June at El-Sawi Cultural Center suggests their hope-infused prediction may yet come true: It was very difficult to find a seat that night, and many people had to sit on the floor or stand at the back of the room.

The why of it all is simple: Egyptians have, throughout history, appreciated Qur’an recitation not just for its divine nature and meaning, but also for its aesthetic attributes. In The Art of Reciting the Koran, published by the AUC Press in 2001, musicologist Kristina Nelson writes: “Although the ideal recitation may not be called music, a certain musicality, such as use of melody and vocal artistry, is not only accepted but required to fill the intent of the ideal. This requirement is based on the recognition of the power of music in general to engage the emotions and thus involve the listener more totally in the recitation.”

While a select group still appreciates the aesthetic values of Egypt’s reciters such as Sheikh Ismail, Abdel Baset Abdel Samad, Mohamed Rifaat, Siddik El-Minshawy and Abdel Fattah al-Sha’sha’ii, more and more Egyptians are shying away from the distinctly Egyptian melodic recitation, most of them motivated by a pernicious conservative undertone in society.

Indeed, religious conservatism is leading some Egyptians reluctant to purchase or seek out this form of recitation, driving them toward drier, less musical forms that originated in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi model of hijab and even thinking has overtaken recitation as well. During Ramadan, we hear recitations that follow the Saudi (also known as the Hudhaifi) model on national television. For many, as Nelson points out, this reflects an artistic vacuum as much as it does a shift in religious attitudes. Egyptian recitation should be viewed as part of the Egyptian identity, which some fear is fast dissolving.

One way to maintain it would be to celebrate our great talents —talents such as Sheikh Mostafa Ismail.

The Followers

Ahmed Mostafa is Sheikh Mostafa Ismail’s biggest fan and collector. Finding his building on the winding and crowded Terat el-Gabal Street was as difficult as finding his specific apartment was easy — the sound of a beautiful Qur’an recitation filled the air. The voice, pure and clear, was unmistakably that of Sheikh Ismail, Egypt’s renowned reciter and arguably one of the most important voice talents of the 20th century.

Ahmed Mostafa, who is said to have over 1,000 live recordings by the late Sheikh, is working hard with the late Sheikh Ismail’s family to keep the star reciter’s memory alive.

Enter the collector’s apartment and you’ll be greeted by a living room full of visitors. Youssri El-Zayet, a friend of Ahmed’s, welcomes us in. I sit next to a young girl by the name of Somaia, who is 10 years old. The famous Qur’an chanter Sayyed El-Qadi sits across from me, as do Somaia’s father, uncle and Qur’an tutor. Ahmed Mostafa, who can’t seem to sit still, flits about turning on more Qur’anic renditions by Sheikh Ismail.

He is too busy doing a number of things at once, and talking to him is proving to be difficult. At last, he sits down and begins helping

Somaia recites the Qur’an. He says an aya (verse) and she copies it, trying to stay within the same maqam. (The maqam refers to the melodic system of Arabic music. A maqam is not a scale so much as a group of pitches that manifest characteristic melodic patterns and some hierarchy of pitch organization, as Nelson describes in her book.) Somaia is here today because Ahmed Mostafa is preparing her for Ramadan, when she will be reciting on Al-Fajr channel, for which he works as a consultant.

“I like Sheikh [Ismail] because he has the most beautiful voice,” she pronounces. “He is a karawan [nightingale]. I like his style and try to sound like him.”

Like Ahmed Mostafa, El-Zayet too is a collector of fine recitation. Unlike his friend who listens to no one and nothing but Sheikh Ismail, El-Zayet can appreciate different voices.

“Ahmed’s father, Mostafa Kamel, was one of Sheikh Ismail’s close friends, and one of his sammee’a [listeners]. Ahmed inherited this love. He literally grew up on the Sheikh’s lap, and would accompany his father to events where the Sheikh was reciting. As a teenager, he took a recorder with him to events, which is where his recordings come from today,” El-Zayet explains.

“Yes, it is true. I do not listen to anyone else,” admits Ahmed Mostafa. “When you get used to his voice, it is difficult to pollute your ears with anything else. My blood pressure goes up if I hear anything else.”

Like Ahmed Mostafa, El-Zayet too is a collector of fine recitation. Unlike his friend who listens to no one and nothing but Sheikh Ismail, El-Zayet can appreciate different voices.

“Ahmed’s father, Mostafa Kamel, was one of Sheikh Ismail’s close friends, and one of his sammee’a [listeners]. Ahmed inherited this love. He literally grew up on the Sheikh’s lap, and would accompany his father to events where the Sheikh was reciting. As a teenager, he took a recorder with him to events, which is where his recordings come from today,” El-Zayet explains.

“Yes, it is true. I do not listen to anyone else,” admits Ahmed Mostafa. “When you get used to his voice, it is difficult to pollute your ears with anything else. My blood pressure goes up if I hear anything else.”

Ahmed Mostafa first met the Sheikh in 1949. “I was nine at the time. I heard him recite Suret El-Kahf [The Cave]. I enjoyed it very much. It was intimidating. People would scream and shout at each repetition, and my father would say ‘Aayy’ in a certain maqam. The Sheikh told me ‘This “ay” would ring in my ear, [shutting out] all the noise of the people.’ My father then taught me the maqamat. At 16, I saved enough money to buy my first recorder. Then I would follow the Sheikh to the Delta and Upper Egypt cities and towns. But before me came a number of fans who made recordings as well. First there was Ibrahim El-Kahky, then Saad El-Dhahabi, and before them were Ibrahim Qassem and Amin Bek Saeed. Today, I have 1080 hours of recordings. The [state-run] Radio has only 12,” he says.

A family affair

On one of Zamalek’s now-crowded streets is the home of engineer Wahid Mostafa Ismail. It was in this apartment that Sheikh Ismail lived before he moved to his famous villa a few streets away. The place of honor in their living room is dedicated to a glass case holding Sheikh Ismail’s memorabilia.

Seeing the emma [turban] and kakoola is, for some reason, a very moving experience. “He wrapped this turban around his head the last time he wore it. It has been kept intact since then,” Amani, Wahid’s wife, tells me.

Many people have tried to understand the genius of Sheikh Ismail’s voice, and Wahid starts to explain why, recalling an evening that took place 50 years ago, when he was 12. “We had some Lebanese visitors at home and they wanted to meet Mohamed Abdel-Wahab [the great musician]. My father asked me to accompany the driver to his house. As I knocked, Abdel-Wahab himself opened the door. He was very tall, and asked me who I was. When he found out I was Sheikh Mostafa’s son, he told me: ‘Do you know that your father is a genius?’ I s ‘Well, people say so’.”

As soon as he turned professional as a teenager, the reputation of the brilliant Sheikh spread from his village to the surrounding villages and from there to Tanta and to the whole of rural Egypt. “Until the early 1940s, my father did not feel the need to go to Cairo. This is why when he was asked to go to Cairo in 1943, he asked for LE 20. He knew that the competition was very severe in the capital, and he was satisfied with his fame so far, but the family agreed to his exorbitant price,” Wahid remembers.

Once he was heard in Cairo, he became the most coveted reciter in the country within a matter of days. His fame was only enhanced after King Farouk heard him on the radio and asked him to recite at the Royal Palace during Ramadan.

But his fame also brought him some enemies. “A certain famous sheikh of the era would refuse to give my father any chance to recite if they happened to be at the same event. He would keep going until everyone left. In one such event, the famous Sheikh Darwish El-Hariri, who taught Om Kolthoum, arrived with a group of artists and musicians, and insisted that my father recite even though it was already midnight and the workers were removing all the chairs in the sowan. My father then recited until 3 am. When he finished,” Wahid remembers, “El-Hariri declared he was the best reciter he had ever heard.”

As fellow reciters came to know the sheikh, they also came to love him.

“All the big names you hear about treated him with respect. Any leila [event] was his leila, and they sat there listening until he finished. He was very polite and soft-spoken and very funny too, which is why everybody loved him,” says Alaa Hosni Taher, his grandson, an EgyptAir flight attendant and a Qur’an reciter who follows in the footsteps of his grandfather, the great Sheikh Ismail.

Imam of Quraa

Taher was 20 when his grandfather died. “I used to go with him everywhere until he died. He knew I could recite, but I never asked him to sit and listen to me. Yet he would often ask me to recite a part he had read in a certain event. He would often be amazed, wondering how he achieved such a difficult note. ‘I wouldn’t be able to say it again if I wanted to,’ he would tell me,” Taher remembers.

Dr. Ahmed Neaynae, the famous Qur’an reader, once told noted composer Ammar El-Shereii: “Mostafa Ismail is not just one sheikh. He is several methods and sheikhs in one. You can find all musical forms in his recitation. Whenever I hear a sheikh say something, I remember that Sheikh [Ismail] had said it before. Reciters have failed to come up with anything new after him. He moves easily between maqamat, and never went off tune. The listener’s ear never feels tired of him, because he always intrigues his listeners. He is creative in his qafalat [endings]. I can often predict qafalat, but his are always unexpected.”

Late great composer Abdel-Wahab was of much the same opinion: “He was big in his art, he was big in his management of his voice, and was the only reciter who surprised listeners with unexpected maqam routes,” he once declared.

In his Dream TV program two years ago, El-Shereii tried to analyze the sheikh’s musical genius by replaying a few short recitations. “His recitation was miraculous, and he was a musical miracle as well. He was unique.”

Analyzing a different verse, the composer says: “He would go up to the very highest notes of the maqam, and he would do it with ease, enjoying himself. It is enough to drive you crazy. This man must have understood music very well, and must have meant what he was doing. He uses saba maqam at first to demonstrate huzn [sadness], then moves to the C, or agam, and then he takes his voice high up the notes when he says al-samaa (the sky) If this were not a musician, then we the musicians know nothing, and must go home. He knew what he was doing and did it depending on his knowledge of the [seven] qira’at [readings] and his very special expressive ability.”

Taher has dedicated most of his time to preserving his grandfather’s heritage by compiling his photos, recitations and everything that was ever written about him.

“He wasn’t called the Imam of Quraa for nothing,” Taher claims. “His genius was in his ever-varying recitation, which changed according to the atmosphere. His reading in Egypt was different from his reading in the Levant, and his reading in Cairo was different from his reading in Alexandria or Upper Egypt. Maqamat change according to the geographic area. In Indonesia, for example, they love the hogaz maqam, and they imitate my grandfather’s hogaz readings. But Sheikh [Ismail] was able to jump from maqam to maqam with great ease and beauty. Om Kolthoum was infatuated with him and would often ask him if he ever learned music. He said no, it is divine work, and just comes to him this way,” Taher says. “This is why he was always tense before any leila. A genius never repeats himself, but improvises as the moment decrees. He often ascended the dekka without knowing what he was going to read.”

A prince of tajwid (the system that codifies the divine language and accent of Qur’anic recitation in terms of rhythm, timbre, sectioning of the text, and phonetics, as Nelson explains), Sheikh Ismail told Nelson that, “The better one can use the maqamat, the more effective one’s recitation recitation without melody is of no benefit.”

He also confided the secret of his method, a method that today is taught to all young reciters. “With a low beginning, little by little [the reciter] takes hold of himself I entered on maqam hogaz with adab [politeness], not a rude awakening, but a polite knock.

‘Who’s there?’

‘Mostafa.’

‘Welcome, etc.’

These are manners, not rushing in on an open door when madam is sleeping.”

These are manners, not rushing in on an open door when madam is sleeping.”

The Sammee’a

Back in Ahmed Mostafa’s apartment, we are joined by Sheikh Sayyed El-Qadi who, as a teenager, met Sheikh Ismail in 1962. El-Qadi believes Sheikh Ismail’s listeners were an important factor in making him what he became.

“Back in the past, the listeners were often as famous as the reciter. Many of them, who were talented musicians like Mostafa Kamel, Ahmed’s father, taught the sheikh the art of maqamat through their comments. This is why Sheikh Mostafa enjoyed reading in mosques or among people more than he liked reading for the radio. His audiences encouraged him, so he knew he was doing well. He enjoyed their comments.”

Taher begs to differ, for he believes his grandfather was in total control of his tools and was often unaware of the listeners, because when he went deep into his recitation he entered an altered state. “I think he affected his listeners, not the other way around,” Taher offers.

Although they may disagree on some points, both believe in Ismail’s genius. And part of his genius was his ability to repeat the same word or group of words several times, each time with a different melody.

“When I do a high passage and feel it is not up to its potential (not ripe), I do it again — still not right — again — OK. I keep repeating until it is good. I am aware of the presence of critical listeners,” Ismail himself explained to Nelson. Which is why a normal recitation session would take him anywhere from 90 to 120 minutes, sometimes even longer. On some nights the Sheikh was known to recite for three to four hours.

Sheikh El-Qadi then suggests that Sheikh Ismail lived in an era where a number of great musical talents existed, such as Abdo el-Hamoly, El-Manyalawi, Om Kolthoum, Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, and great reciters like Mohamed Rifaat, Mansour Baddar, Abdel Fattah El-Shaeshaey and others. “He had listeners who could move stone, and an atmosphere that encouraged uniqueness. It was a beautiful era. He had to come up with something new,” he explains.

El-Qadi’s words are blasphemy to Ahmed Mostafa’s ears. “Do you think El-Bahtimi, El-Minshawi or El-Seifi had it in them to recite like Sheikh [Ismail] and did not? His talent was divine, it came from above. They were nothing like him,” he interjects heatedly.

At this point his guest starts getting angry. “I have nothing to do with what you are saying. Seriously, this is not a joke. I do not like those who treat the Sheikh like the Ahly or Zamalek clubs. Let’s be serious, Sheikh Mostafa was surrounded by beauty. When I have to recite some ibtihalat [religious chants] for the fajr radio broadcast, I try to busy myself with my absolutions so I do not have to listen to the reciter preceding me. It ruins your hearing. Sheikh Mostafa must have benefited from his era,” El-Qadi charges.

Haram or halal

The new musical forms he came up with sparked an even more heated debate questioning the appropriateness of his style to a sacred text like the Qur’an. “The late Sheikh Mostafa Ismail was considered suspect as a reciter by many Muslims because of his extreme musicality. But one devout scholar [Dr. Hasan El-Shafei] told me that, although he used to think that Sheikh [Ismail] was ‘too musical’ he had come to accept him because he realized that Sheikh [Ismail] knew his tajwid; “There is no denying the musicality of the religious text, and as long as tajwid is used, and music does not distort tajwid or distract from the text, it is acceptable,” wrote Nelson.

“Sheikh Mostafa himself told me that when asked about the reluctance to associate Qur’anic recitation with music, he responded, ‘as long as the rules of tajwid are adhered to, the pauses are correct, the reciter can recite with music however he wishes.’ This statement was broadcast over national television on the program Your Favorite Star with the ‘Imam of Al-Azhar, the president of the republic, and countless others listening,’ and Sheikh [Ismail] said he challenged anyone to disagree, but never heard a word of rebuttal.”

Sheikh El-Qadi is quick to recite a number of hadith to prove that Islam actually demands the Qur’an be recited with melody. “If a verse is read by a scholarly reciter who has studied then he will say the words right even if they are melodious. When you come to think of it, we use melody in our speech. Does this take away from it or add to it? The thing is not to forget the sacredness of the Qur’an, which Sheikh Mostafa never did.”

The Future Sheikh

A young man sits next to Sheikh El-Qadi. His face seems familiar, and I find out he is Yasser El-Sharqawi, a 20-year-old and already a rising star in the world of Qur’an reciting. Ahmed points him out, “Yasser is going to become a big star, don’t you think so, ya Sayyed?” The Sheikh nods his head. Yasser looks down in obvious embarrassment as he blushes profusely. “He sounds just like Sheikh [Ismail] to the untrained listener. Just the fact that he puzzles you a little is an honor enough for him. He will definitely fall after a while, because Sheikh [Ismail] was a gift from God,” Ahmed adds.

El-Sharqawi is fast becoming known through Al-Fajr channel; he’s a devout fan of Sheikh Ismail, and rarely listens to other reciters.

“Sheikh [Ismail] is unique, and very modern. His style is his own, and the melodies he recites once he never recites again,” he says. Three years ago he met Ahmed, who was impressed by his voice and decided to help him become a better reader. “He helps me manage my voice. He teaches me how to start with bayati, then go up (the scale) slowly, then go down again and then warm up to the high notes once more,” El-Sharqawi says.

His dream is to become a renowned reciter, his chosen profession, which he plans to take up fully after he graduates from Al-Azhar’s faculty of Shariah and Law. Whether it is a lucrative enough business is an open question. El-Zayet says that thanks to famous reciters alive nowadays, such as Sheikh Tablawi, a reciter can charge anywhere between LE 700 and LE 10,000 per night, depending on how famous he is.

El-Sharqawi has passed his tests at the Egyptian Radio and Television Union’s Quraa committee, where he explains he tried to come up with new forms for recitation: “I do not imitate Sheikh Mostafa. Although I love him and I belong to his school, I also try to come up with something new, just like he did.”

The young reciter is going to spend this coming Ramadan in Germany, where he will celebrate the Holy Month with that country’s Islamic community.

The young reciter is going to spend this coming Ramadan in Germany, where he will celebrate the Holy Month with that country’s Islamic community.

He recites some verses for us. At first, he gave us a rendition of Surat Al-Doha in the murattal style (faster, less melodious than tajwid). Afterwards, he continued in the tajwid style. His recitation moved everyone. Ahmed kept shouting “Allah ya walad ya Yasser!” every time the young talent improvised well, which reminds him of the live recordings he has of Sheikh Ismail’s readings.

Every time he showed his appreciation, El-Sharqawi’s reading seemed to improve. The relationship between a reciter and his listeners has rarely been clearer.

Coveted memories

Those who may want to hear for themselves face one mammoth obstacle — there are hardly any recordings of the Sheikh’s heritage. Only 18 tapes are available at Sawt El-Qahira. “We have some financial problems with them, which is why they do not print enough of Sheikh Mostafa’s work,” his son Wahid says. Taher points out that also available on the market is the complete mus-haf (Qur’an) in the murattal style, which makes it easier for students to follow and study. But the rare live recordings, which collectors savor and boast about, are very difficult to come by.

And it’s not just his recitations that seem to be lost. Where is his beautiful azaan? Why do we never hear it on television? Queries Wahid. “Where are the 700 tapes the radio has by him?”

According to the Sheikh’s family, we are now witnessing an era of decline. “But it will end, and then people will start looking for my grandfather’s work,” Taher believes.

Wahid too is confident of this. “My father once said to me, ‘Do you know? One day, people will appreciate your father,” he tells. That was at a time when Sheikh Mostafa was met by heads of state wherever he went, and people treated him like a superstar when he walked down the street.

Ahmed Mostafa is as guarding of the Sheikh’s heritage as his family. He willingly copies out tapes to friends and acquaintances, making use of his extensive sound equipment, which he uses for nothing except the works of the reciter.

In the meantime, the Sheikh’s family holds on to the extensive rare recordings they own. “Now is not the time to release them. People are not ready. We want the young people to know who Sheikh Mostafa is, and we are looking for the way to do it right,” Wahid ends. et

Copied from: