Somaya Edeeb, Yaser Sharqawi and Ahmad Mustafa are in Turkey for Ramadan and will be reciting in many programs across Turkey.

Here is one from the Ibo Show that broadcast a few nights ago:

Art of Recitation Site Pages:

-

►

2007

(13)

- ► February 2007 (8)

- ► March 2007 (2)

- ► September 2007 (2)

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Ramadan Kareem - New Videos

Posted by

A Reciter

at

6:12 PM

![]()

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Qari Ahmad Naina - US Tour

Qari Ahmad Naina was touring the US in June. Please contact me if you would like more info on his programs, the videos or if you would be interested in having him recite in your city.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

9:43 AM

![]()

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Ramadan Videos - Sh. Mohmd Jibreel 2007

Salam Alaikum Everyone. I hope all of you are in the best of health and blessings during this amazing month.

Here are some videos that you may not get living in the US but reflect some of the programs muslims are watching in other countries. This may help you get more in the mood of this month and also view some beautiful recitation and supplication.

For those of you that may not know who Mohmd Jibreel, he is the oficially appointed reciter of Amr Ibn al-Aas mosque in Cairo Egypt. He travels extensively worldwide in particular during Ramadan but the rest of the year he is mostly in Egypt. He lives in Muhendiseen and I have had the pleasure of sitting with him at home and learning from him about maqamat and other aspects of recitation.

His website is : www.jebril.com

Below are videos of Mohmd Jibreel before coming to the US this month. He is reciting the Qur'an on the "Cairo Today" television program.

Mohmd Jibreel is in my opinion one of the best Murattel reciters living today.

One of the reasons why he is so unique in his recitation is in that he changes his tone and mode with meaning. This does require him to sometimes recite slower than typical Murattel reciters but it creates a much more engaging recitation.

Observe for yourself. Here from Surat Shura:

Here is reciting from Surat Qaf:

Short Dua (supplication):

And here he is again with a very nice dua (supplication)in this blessed month.

I hope you enjoy.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

2:15 PM

![]()

Thursday, September 20, 2007

Surat al Kahf with Sumaya

Here is a video of Surat al Kahf recited by 5 young girls on Friday. It also contains many hadith and details that explain the Surah. The video is in Arabic but is enjoyable for even a non Arabic speaker.

This is an excellent video for :

1. Reciting every Friday as there is great reward in it.

2. Using for memorizing the Surah.

3. As motivation for young girls who will be good reciters one day.

This video was given to me by Sumaya's family when I was visiting them recently, May Allah reward her and them greatly.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

10:23 AM

![]()

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

Friday, March 2, 2007

Maqamat - Arabic Musical Modes

When it comes to understanding Maqamat the context of what is written here is about vocal Maqam. The human voice is much more important than any instrument. The musician needs to think how to make the sound on an instrument whereas a singer can spontaneously make the sound without a need for tuning.

The Maqamat are 7 in their roots or foundations. Each Maqam is said to be a street or a way. Each Maqam also has its branches or derivations and examples of this will be given later.

Example Lessons on Maqamat

In order to understand the Maqamat, it is necessary to know the scales of Arabic Music first. Here is a quick overview of the 'darajaat'or 'scales' :

Maqam Bayati - maqam used for gentleness, light joy, vitality,

Maqam Rast - masculine, power, soundness of mind,

Maqam Rast - Jawab (High Tone)

Maqam Saba - literally in Arabic, baby boy; used for sadness, tragic, lamenting, pain

Maqam Hujaz - which is named after a region in arabia; distant longing, desert, solemn,invocation

Maqam Nahawand - named after a city in Iran, resolution, seriousness, discourse

Maqam Nahawand- Jawab (High Tone)

Maqam Seeka - from the Persian for "third place", serious, love

Maqam Jiharkah -

Maqam Ajam - named after the Arabic word for "Iranian", is used to mark happy occasions such as holidays, weddings, and other joyous occasions

Posted by

A Reciter

at

4:46 PM

![]()

Ethics for the Recitation and Listening of the Qur'an

First about Reciting.

Imam al Ghazali has pointed out vital actions that a person should adhere to when he recites the Qur'an:

- Understanding the glorification of the literal words of Allah. (Be aware of what he is saying)

- Glorify the speaker (of the Qur'an)

- Being aware of and abandoning any inner thoughts or calls that are made by the self or other

- Thinking and pondering over the subject of the ayat being recited

- Knowing the meaning of the ayat being recited

- Avoiding the following: Too much concentration on the pronunciation of the letters to the detriment of understanding the ayat. Blind imitation of a school of thought ;Persistence in sin because of pride and slavery of passion

- Considering every part of the Qur'an being read is meant personally for the recite

- Developing internal feelings hope and grief/fear of the message being recited from the Qur'an.

- Creating the impression that the reciter is hearing te literal words of Allah from Allah and not from himself.

- Avoiding any sense of reciter's ability and power by looking at himself with a feeling of satisfaction or purity above the words being recited.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

2:43 PM

![]()

Monday, February 26, 2007

Somaya Abdel Aziz (Qari'a)

Somaya Abdel Aziz is a new talent that has appeared in Egypt recently. She is a young 12 year old girl from the town of Benha between Cairo and Tanta in Egypt. She is the eldest daughter in a great family of truly kind people. I was recently in Egypt in order to meet with some reciters when I was shown her video by Ostaz Ahmad Mustafa. I was very impressed to see her talent and ability at such a young age. I asked to see if I could meet with her and her family and they were extremely welcoming and hospitable. There I met with her two other brothers and sister and all of them are excellent reciters and memorizers of the Holy Qur'an. I then asked her to recite some ayat which she did impressively. Don't take my word for it, see for your self below:

Posted by

A Reciter

at

11:03 AM

![]()

Sh. Helbawy - A Great Teacher of the Art of Recitation

Sh. Mohammed Helbawy is the last of the great teachers of the art of recitation of the Holy Qur'an. Not only this but he is even more accomplished in Ibtihalat and Nasheed (Islamic Music). He is an Azhari scholar with specialization in 'Qira'at'.

One of the things that struck me most about this man was that even as accomplished as he was he was never arrogant nor aggressive in his dealings with me, I always found him very kind, supportive, and humble. In a day and age when many of the reciters you deal with are only after fame and money I found him to be totally opposite. He was concerned with doing his best to help me out of his care to please God.

When I was with him on one of our classes I asked him about the permissibility of accepting large amounts of money as compensation for reciting the Qur'an. He answered by telling me about how he asked this question to Sh. Shar'awi the recent prominent Egyptian scholar who passed away.

Shaikh Sharawi said that the permissibility of accepting money (or hadiya) for reciting the Holy Qur'an has 2 circumstances and conditions.

1. The first is if one is to recite the Quran upon a request then there should be no discussion of money beforehand with the host (requestor). After the recitation whatever the amount of money is that the host gives should be taken with no objections. If this is done then the money will be a reward in the duniya and the act of reciting will also be rewarded with Allah in the hereafter (akhira). This is the prefered circumstance.

2. The second is when one is requested to recite the Qur'an and before reciting he asks for a certain amount or negotiates an amount with the host. After the recitation the reciter expects an amount previously agreed upon to be paid. In this circumstance there is only payment in this life(dunya) and there will be no reward in the hereafter(akhira) for this action. This is the lower level of the 2 circumstances.

Interestingly today the most common circumstance is the second. But this has not always been the case, many of the great reciters of our past would be more concerned with their wealth of the hereafter before being concerned with their wealth in this world.

Here is Shaikh Helbawy teaching me through Suratal Muzammil examples of Maqam Bayati, Hugaz, and Nahawand:

I am currently looking for any people interested in inviting Sh. Helbawy to the US. If you are in the US and may be interested please contact me at areciter@yahoo.com.

For More information on Sh. Helbawy see:

http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/music/news.cfm?story=34330

http://www.ualberta.ca/~ethnomus/PastEvents/helbawy.htm

A good site of a good brother I know that has some of his recordings is:

http://www.islamophile.org/spip/article364.html

Posted by

A Reciter

at

10:19 AM

![]()

Sunday, February 25, 2007

Shaikh Yaser Sharqawi

If you want to know how talented Yaser Sharqawi is then watch this video in which he demonstrates the major maqamat in the way of Sh. Mustafa Ismael.

Here is a great video of this same night in the Saloon of Ahmad Mustafa.

Here Ahmad Mustafa is beginning an ayah in a particular maqam and Yaser is expected finish the ayah or the maqam. This is a good demonstration of how Ahmad Mustafa also teaches or directs the reciter.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

10:12 AM

![]()

Friday, February 23, 2007

Saloon Ahmad Mustafa

Yasir Sharqawi

Somaya Abdel Aziz

Momen Mahmood

and others...

Posted by

A Reciter

at

9:02 PM

![]()

An Update

Some of the information posted here will be more of my first hand accounts in learning in this field with various teachers and reciters and my interaction with them. Some of the reciters I have personally had alot of influence from and who you will find more information about are:

1. Sh. Mustafa Ismael

2. Sh. Mohammed Refat

3. Sh. Kamil Yusuf Bahtimi

4. Sh. Ali Mahmood

5. Sh. Mohammed Omran

6. Sh. Hamdi Zamel

Alhamdulillah I have had the opportunity to learn from or spend time with some renowned reciters of our time who you will also find more about on this blog:

1. Sh. Muhammad Al-Helbâwî Ash-Shâdhlî

2. Sh. Ragheb Mustafa Ghalwesh

3. Sh. Mohammed Gebril

4. Dr. Ahmad Naina

5. Qari Syed Sadaqat Ali (Pakistan)

6. Sh. Mohammed Basyuni

Posted by

A Reciter

at

5:21 AM

![]()

Special Tribute to Shaikh Mustafa Ismael

Also I would like to pay special tribute to Shaikh Mustafa Ismael, a reciter who I feel has had the most impact in the field of Quranic recitation during the last 50-100 years. He has left behind many fans, enthusiasts, and imitators in all parts of the world such that his legacy still thrives today.

On this note I plan to also post many videos and pictures of the 'Saloon Ahmad Mustafa'. A place that has become the 'musical' school of Mustafa Ismael in Masr Gadeed/Cairo. It is a place where many great reciters and enthusiasts come to discuss, listen, and learn about Sh. Mustafa Ismael.

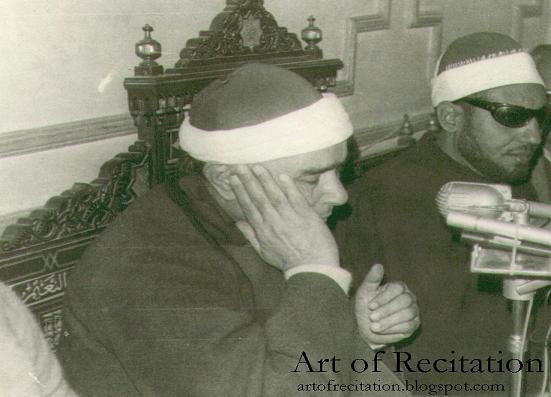

A rare picture of Sh. Mustafa Ismael.

Here is good article that talks about people I will profile in future posts:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Once, Sheikh Mostafa Ismail’s recitation of the Qur’an was enough to stop anyone in their tracks. Today, on the centenary of his birth, his followers are struggling to keep alive his tradition of melodic recitation. Will religious conservatives relegate an Egyptian tradition to the dustbin of history

One day, a stranger happened to be passing through the village of Mit Ghazal in Gharbeya governorate when he heard the voice of a little boy reciting Qur’an at a kuttab. The man stopped, then took the boy home, along with his tutor, to speak with his father, where he advised the father to keep teaching the child the Qur’an because he was going to become one of the best reciters in recent history.

This year marks the centenary of the Sheikh’s birth (he came into the world on June 17, 1905), and while the anniversary has not been celebrated by the official media — except in a short segment on the daily talk show El-Beit Beitak — Sheikh Ismail’s fans and family are certain that the future will only bring more appreciation of his musical genius.

Like Ahmed Mostafa, El-Zayet too is a collector of fine recitation. Unlike his friend who listens to no one and nothing but Sheikh Ismail, El-Zayet can appreciate different voices.

“Ahmed’s father, Mostafa Kamel, was one of Sheikh Ismail’s close friends, and one of his sammee’a [listeners]. Ahmed inherited this love. He literally grew up on the Sheikh’s lap, and would accompany his father to events where the Sheikh was reciting. As a teenager, he took a recorder with him to events, which is where his recordings come from today,” El-Zayet explains.

“Yes, it is true. I do not listen to anyone else,” admits Ahmed Mostafa. “When you get used to his voice, it is difficult to pollute your ears with anything else. My blood pressure goes up if I hear anything else.”

These are manners, not rushing in on an open door when madam is sleeping.”

The young reciter is going to spend this coming Ramadan in Germany, where he will celebrate the Holy Month with that country’s Islamic community.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

5:16 AM

![]()

Saloon AM - Yaser 1

Here is a quick video of a recent night I had in the house of Ahmad Mustafa. In this video Yaser Sharqawi is being prompted by his teacher Ahmad Mustafa on the beginning of an ayah and Yaser is finishing. Yaser Sharqawi is an amazing talent that is becoming a rising star in Egypt.

Posted by

A Reciter

at

4:53 AM

![]()

Thursday, February 22, 2007

First Post - The Art of Recitation

The hope of making this blog is to provide you with knowledge and examples of how to better recite and listen to the Qur'an through many master reciters of the past and some of our present. In particular I will focus on the egyptian reciters because they are so rich in this field.

Some good reading until this site becomes more full of information:

God's earthly tones

The Art of Reciting the Qur'an, Kristina Nelson, Cairo and New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2001. pp246

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Some three weeks ago, at the Sidi Abul-Ela Mosque in Bulaq, while devotees of the saint solicited his intercession at the shrine, a large group of people gathered in clusters all across the main courtyard, listening to the sound emanating from half a dozen or more ancient-looking speakers positioned at convenient spots throughout. Although the sound was far from excellent, many had brought along recording equipment. There was something almost surreal about the scene. Young and old, conversing intermittently in whispers, these people had obviously gathered there for a purpose, but to the hapless observer, on walking into the mosque, that purpose was far from clear. In comparison to other, simultaneous events in Bulaq, moreover, the atmosphere of the Abul-Ela Mosque was remarkably quiet; and whatever activity taking place there seemed to be correspondingly low-key. Only after sitting cross-legged in one corner did it finally dawn upon the observer in question that he, too, had arrived there for a purpose: the event was a commemoration of the anniversary of the famous Qur'anic reciter Shiekh Mustafa Ismail (1905-1978); the speakers supplied rare, otherwise unavailable recordings of his recitations; and the listeners were aficionados. It was a sad irony that the reciter who once commanded a phenomenal popularity in this neighbourhood should be remembered so quietly by so comparatively few people. Yet the scene also afforded a glimpse of the power and majesty of a tradition that has come to be all but extinct: the art of reciting the Qur'an, the subject of the present book. Matching text to melody even as she delineates the received rules of recitation -- the book benefits from a precise system of transliteration as well as musical notation -- the author brings to this comprehensive account of Qur'anic recitation a range of epistemological perspectives, combining her knowledge of music and language with an exploration of the minds of the likes of Shiekh Mustafa and his admirers, and the circumstances in which they lived and worked. For a study of such diversity, moreover, the book is meticulously structured, making for a straightforward, if frequently taxing, read. An anthropologist, an expert on Arabic music and a Qur'anic scholar will each find both stimulation and benefit here.

"Night falls as small groups of people make their way towards a large tent straddling a Cairo street," Kristina Nelson, a scholar of ethnomusicology and a seasoned, active participant in the cultural scene of the Arab world, writes in her introduction to The Art of Reciting the Qur'an, the fruit of many years of research and first-hand encounters with reciters, listeners and scholars, first published in 1985 by the University of Texas. "As they draw near, a clear ribbon of sound begins to separate itself from the dense fabric of street noise all around. The sound is that of the recited Qur'an; a public performance has just begun." Since the present edition of the book was published, it is this passage, along with the rest of the introduction, that has been quoted most extensively by the Arabic press -- an indication, perhaps, of the appeal of the introduction as a condensed summary of the entire project, as opposed to the more specific scholarly orientation of the book's various chapters. One aim of the study, for example, is "to examine the implications of a particular perception within its tradition: given that recitation is the product of both divine and human ordering, how does this juxtaposition work in the mind of the performer and in the expectations of the listeners to shape the recitation of the Qur'an in Egypt today?" Classified by "those outside the tradition" as a form of religious music, recitation nonetheless remains, for those inside, both "distinct from music" and "a unique phenomenon." It is always to the heart of the tradition that Nelson thus turns in her attempt to demarcate the territory occupied by that "clear ribbon of sound," which initially enthralled her. "My own interest in Qur'anic recitation was caught and held by the power of the sound itself," she testifies. And to pursue that interest, Nelson has crossed geographic, cultural and linguistic borders. She studies the theory of recitation, the (rightful) place it is meant to occupy in Qur'anic cartography, in order to reach back to her experience of its practice. "A man hides his face in his hands," the introduction goes on, "another weeps violently. Some listeners tense themselves as if in pain, while, in the pauses between phrases, others shout appreciative responses to the reciter. Time passes unnoticed..."

Ethnomusicology is a multidisciplinary arena that makes possible the exploration of "the link between the affective power of sound and its referent meanings in daily life and religious practice." As a female Westerner, Nelson was thus confronted by the twofold difficulty of coming to the sacred realm of Qur'anic scholarship from a profane (musical) background, and being the lone foreign women in a world made up exclusively of native men. Looking back on her experience -- Nelson spent the period from September 1977 to August 1978 in Cairo undertaking research of a journalistic as well as a scholarly nature and learning the two modes of recitation, the private, devotional tartil and the artistic, audience-oriented tajwid -- she wonders whether this "completely crazy" task would have been possible had she started her project in the 1990s, a time of decline for both the traditions of recitation and the tolerant attitudes that make social integration possible. It was the humane eagerness of these men, after all, that sustained her "desire and intent" to complete the task: "everyone I met in the course of my research," Nelson recalls in the Acknowledgments, "was extremely helpful and generous with time, information, and hospitality." This spirit of intercultural integration informs not only the project but the book, in which Nelson was careful not to fall into the trap of Orientalism by substantially referencing every point she desired to make. "The way to do it," she has confided, "is to let the relevant people say it for you rather than saying it yourself; this way it doesn't sound like something you're imposing." In itself this (Western) orientation is a commendable achievement: at no point does the desire and ability to explore a subject of interest imply a superior or authoritative attitude. Nelson is as faithful to the given precepts of Islam and Muslim culture as she is to the dictates of her own (academic) endeavour. And in this sense The Art of Reciting the Qur'an sets a precedent for Western studies of "the Orient" in that it is driven by genuine respect for that realm. Despite such intimate contact, moreover, Nelson has not converted to Islam -- further testimony to the impartial understanding that informs her approach to the tradition of recitation.

Clockwise from top: Shiekh Mustafa Ismail, the "diva" of recitation; Sheikh Mohamed Mahmoud Tablawi; Sheikh Lotfi Amer; Sheikh Abdel-Baset Abdel-Samad; sheikh Mohamed Rifaat; the wajid of one listener; the author among reciters, at the time of conducting her research

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Based on a University of California at Berkeley dissertation, for which the research was undertaken, the book progresses in two closely interrelated directions, seeking, first, "the ideal recitation" in the context of the place of this phenomenon in religious discourse and, secondly, the contemporaneous practice of Qur'anic recitation as Nelson encountered it in real life. The choice of Egypt, she explains, finds justification in "the particular prestige and influence of the Egyptian tradition in Qur'anic recitation, which make it an obvious starting place." And the relevance of her study -- an invaluable contribution to the body of available knowledge on social, cultural and artistic life in Egypt -- is that, unlike the "classic works of Western Qur'anic scholarship," which concentrate on the Qur'an as a written document, it addresses those aspects of recitation on which traditional Islamic scholarship has remained silent: "as the scope of Qur'anic disciplines has been firmly and authoritatively established and that body of knowledge has traditionally been considered fixed and given," in recent times "there has been a reluctance to look at the Qur'an in new ways." The book's importance derives, Nelson implies, not only from giving equal consideration "to the theory and practice of recitation and the analysis of their interactions," but from "my own direct participation in the tradition as student and performer." A thorough consideration of what Nelson calls "the Sama' Polemic," the "alliance of Qura'nic text and vocal artistry" that provides the basis of the historical debate concerning whether and to what extent the melodic recitation of tajwid may be associated with music, follows her impeccable account of the Qur'an itself, the history of the revelation and how the Prophet's message was communicated, as well as the nature of tajwid, Nelson's principal interest. Then comes an account of the ideal recitation gleaned from classic Islamic scholarship, followed by the material of Nelson's own experience: the nuances of the practice of recitation and the dynamics of reciter-audience interaction. Finally "the separation of music and recitation" receives its share of exploration: "That the acquiring of musical skills is left up to the individual reciter," Nelson explains, "is one way to effect a concrete separation of recitation from music," keeping recitation within the framework of religion even when it approaches the intensity of a (musical) performance.

Two interrelated issues make The Art of Reciting the Qur'an of particular interest to those inside the tradition: recitation as a means of transmission of the holy text, and the religious validity of the musicality of recitation. By recounting the history of recitation as the earliest and most widespread means of transmitting the sacred text, Nelson challenges the notion -- so rampant in modern Egyptian society -- that the sacred is the property of a literate minority. Sound emerges as something over and above both music or reading out loud: "The ideal recitation is a paradox. Participants in the tradition... all agree first, that the Qur'an is paramount in its divine uniqueness and perfection, and second, that melody is essential to the most effective Qur'anic recitation. The inherent contradiction between these two premises is accepted, even unquestioned, as long as the right balance of elements is maintained." It is through recitation, after all, that illiterate Arabic-speaking Muslims -- a sizable portion -- come in contact with the text that forms the central proposition of their lives. The concept of taswir al- ma'na (picturing the meaning), the religious justification for melody, thus comes to play a central role in the public transmission of the Qur'an: "The late Sheikh Mustafa Ismail was considered suspect as a reciter by many Muslims because of his extreme musicality. But one devout scholar told me that, although he used to think that Shiekh Mustafa was 'too musical,' he had come to accept him because he knew [the rules of] tajwid... Shiekh Mustafa himself told me that when asked about the reluctance to associate Qur'anic recitation with music, he responded, 'As long as the rules of tajwid are adhered to, the pauses are correct, the reciter can recite with music however he wishes.' This statement was broadcast over national television on the programme 'Your Favourite Star,' 'with the imam of Al-Azhar, the president of the republic and countless others listening,' and Shiekh Mustafa said he challenged anyone to disagree, but never heard a word of rebuttal." Indeed, in the best mujawwad recitations, divine truth is experienced through a unique convergence of elements -- musical as well as textual -- that transcends, rather than underlines the issue of whether recitation is a form of music. Shiekh Mustafa's apparently cursory declamation reflects his appreciation of this notion: in his endeavour to transmit the divine text, the reciter should resort to whatever human means he is capable of, the better to achieve an effective communication of its meaning.

Music, in other words, cannot sensibly be thought to undermine the authority of the text; and however extensive its use, so long as the received rules of recitation are abided by, it cannot reduce the scope within which the experience of the Qur'an is said to be an encounter with the divine; rather, through taswir al-ma'na, it enhances it. Yet in the time she has spent in Egypt since the late 1970s, Nelson has noted a decline in the popularity of tajwid and the cult of "star" reciters, like Shiekh Mustafa, who practised it. And in the Postscript to the present edition of her book, she attempts to address this unfortunate decline: "perceptible changes would seem to indicate that a number of factors have succeeded in moving Qur'anic recitation away from the contested areas of melody and personality cult and that the sensibility that values conscious use of artistry to enhance the effect of recitation can no longer be taken for granted." The Saudi influence that informs the popular recitation of such Egyptian practitioners as Shiekh Mohamed Gibril notwithstanding, the implications of the aforementioned changes include "a more socially and culturally conservative constituency" as well as the rise of "a younger generation... charged with the spirit of an activist Islam" that has no use for artistry. For many of Nelson's contacts, indeed, the period from 1978, the year of Shiekh Mustafa's death, to the present "represents the waning of the golden age of Egyptian reciters." This change moreover reflects "an artistic vacuum, as much as any shift in religious attitudes;" and indeed, since the last decade yielded nothing comparable to Shiekh Mustafa, it may be that the decline of recitation is not ultimately due to the prevalence of the view that takes issue with the musicality of the tradition in the Sama' Polemic, but simply to the unavailability of a generation of reciters who could bring the tradition back to life. After all, tajwid, an already fully lionised tradition, continues to thrive on the radio and on television screens as well as in public spaces. The decline in the popularity of tajwid is naturally conditioned by changes in the social and cultural fabric of life as well. Perhaps, like the bards of the Hilaleya epic and the masters of shadow puppet theatre, the maestros of tajwid too are fast becoming something of the past. And in this sense it is cheering to know that, however marginal and lacklustre their status, there will always be a group of people gathered, however quietly, in venues like the Abul-Ela Mosque, to bear tribute to their majesty and power.

Copied from: http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2002/568/bo4.htm

Posted by

A Reciter

at

3:04 PM

![]()